About Brock

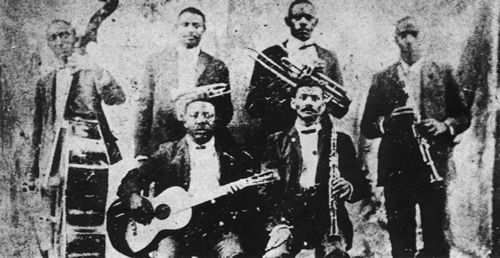

The most famous photograph of the band, taken in circa 1894, shows Brock seated in front of Bolden.

“The Old Cow Died, and Old Brock Cried”

– a song central to The Bolden Band’s repertoire. It’s remnant lives on in Muskrat (Muskat) Ramble.

His jacket appears too small for his frame, an incongruous little bowtie strains to hold his collar closed around his thick neck and shoulders. His parlor guitar juts out, low-slung and haphazard across his right knee. Certain musicians maintain an almost naked, childlike quality to their technique: Their hands, no matter how capable of flights of staggering virtuosity, appear to be touching the instrument as if for the very first time. The body concedes no adaptive curve to its instrument. The guitar appears like a small bird the hands of giant; he seems unsure whether he might crush it, but the affection is undeniable.

The death of the “Old Cow” was almost certainly a metaphor for the death of an agrarian and rural economy, which would, in turn, herald the birth of a new industrial landscape – a terrain marked by the relocation of the worker away from the home, and the workplace itself to concentrated urban areas. Brock’s tears were likely shed both for the death of the 19th century, and a personally conflicted American identity.

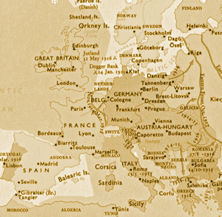

With no “Cow”, no mule, and no forty acres, Brock set out for the European “motherland” circa 1911. Just as a human can get nourishment from a cow’s milk, this found new found youth, identity, and love, suckling at the very bosom of the Old Country. Together they would cross the threshold into the 20th century.

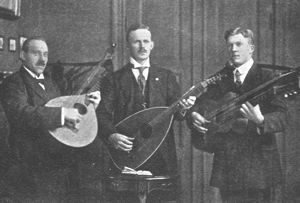

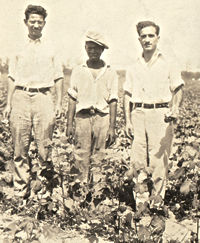

Much of Brock’s time in New York City, prior to his trans-Atlantic journey, was spent in the company of Bowery musicians. I Piccoli Pignoli (The Little Pinenuts) was the band of string virtuosi, the Pino brothers, pictured here in 1912. Collogiero Pino possessed a right hand that was doubtless to be a huge influence on Brock. His technique set a standard for the next wave of Italian American virtuosi including Giovanni Vicari, Frank Frazio, and Giovanni Gioviale.

On board the Ile de France – and later the other great liners La Bourdonnais, the Berangaria, the Mauretiana,

and the Aquitania – Brock found a new vitality and vigor as he awakened passengers, crew, and musicians to the sounds of Jazz and Blues.

No one was immune to the new rhythms, as this cook from La Bourdonnais can attest to. One can only speculate as to the effect Brock had on La Grande Cuisine!

Joseph Wechsberg recounts his own first exposure to the Hot Jazz of The American Negro, along with his initial voyage to America -as a ship’s musician onboard La Bourdanais – in his book “Looking For A Bluebird.”

Once on the continent Brock found the native stringed instrument players

skeptical but willing to entertain his musical ideas.

Prowling the Rue Pigalle and Monmartre in Paris, Brock was able to hear and play with the accordeoniste who were then emigrating from the south and east and bringing their mazurkas, waltzes and tarantellas with them. There would seem to be no reason to suspect that he was not heard by the very young Gus Viseur and Guerino, and the banjoist Gusti Mahla.

Prowling the Rue Pigalle and Monmartre in Paris, Brock was able to hear and play with the accordeoniste who were then emigrating from the south and east and bringing their mazurkas, waltzes and tarantellas with them. There would seem to be no reason to suspect that he was not heard by the very young Gus Viseur and Guerino, and the banjoist Gusti Mahla.

Historians are now almost unanimous in their assertion that he fell in love;

came to regret it; and lived to love again.

Starting out as her guitar tutor, Brock began a professional and personal relationship with the dance hall star Marie Sylviac. His Marie became his muse, and perhaps his Great Love. Their tumultuous affair left many dramas in its wake: The above card contains a mirror written note to her lover after a particularly pungent betrayal – “are you still angry?” it asks.

By the outbreak of The Great War, Brock had become a major cultural icon in France. A popular postcard of the time depicts the innocent courtship and play of a giddy world at the top of the twentieth century: Brock, as the nascent New World, is being extended the girlish hand of aristocratic France.

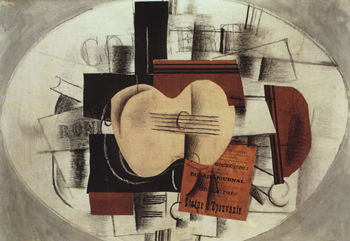

Stunned by Brock’s easy juxtapositions of rhythmic and tonal shapes and colors, George Braque embraces the ideas – and the name – of his “phonetic cousin,” and brings the guitar front and center into cubism with his 1913 masterpiece La Guitare.

It would be decades before La Guitare would return the favor to the cubists in the form of the Flying V, the Explorer, the Steinberger, and most notably, the Bo Diddley.

After 1918 Brock never returned to his place on a national stage, and in fact, as sightings of his gentle face around the twisted streets of Monmartre became all too rare, even the tracks of his personal history seem now to have evaporated. The most likely scenario is that he returned to the ships, oceans, rivers, trains and other points of dissemination and flux where his art had always found its greatest rewards.

Marie continued to increase her proficiency at guitar, and to find love once again. And again.

In the late 1920’s the Pinos traveled to the American south, to learn about the blues that Brock showed them. Despite ceaseless inquiries their friend cannot be found.

In the late 1920’s the Pinos traveled to the American south, to learn about the blues that Brock showed them. Despite ceaseless inquiries their friend cannot be found.

Brock has left us a confusing musical legacy. During a deathbed interview in 1972 the youngest Pino brother, Maurizio, spoke emphatically of “his wonderful hands, such joy! Such rhapsodies! Brock would sing the wordless song of a thousand angels as they dreamed a dream of quivering harp strings! Oh the blues! Those wretched, beautiful, beautiful shimmering blues!”

It would seem that the stunning obbligatos of Mike McKendrick, Snoozer Quinn, and Eddie Lang likely had their roots in these improvisatory flights.

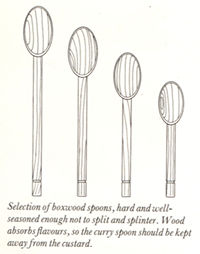

Still another impression is given by the popular jazz guitar pioneer Lonnie Johnson, who in 1968 had this to say to an interviewer from the Library of Congress:

Still another impression is given by the popular jazz guitar pioneer Lonnie Johnson, who in 1968 had this to say to an interviewer from the Library of Congress:

“Yeah, I saw Brock Mumford. I saw him with Frankie Dusen’s Eagle Saloon band in Storyville. Must have been 1906 or there abouts. Why you asking ‘bout him? He wasn’t no guitar player – matter of fact, I don’t think he even put strings on that old box! No sir, he was just hitting on the thing. Hitting it with something. Think it was a spoon. Some kind of spoon. Maybe a big wooden spoon. I think Dusen just kept him around the same reason Bolden did; he was a good mule driver. Could get you to the gig on time”.